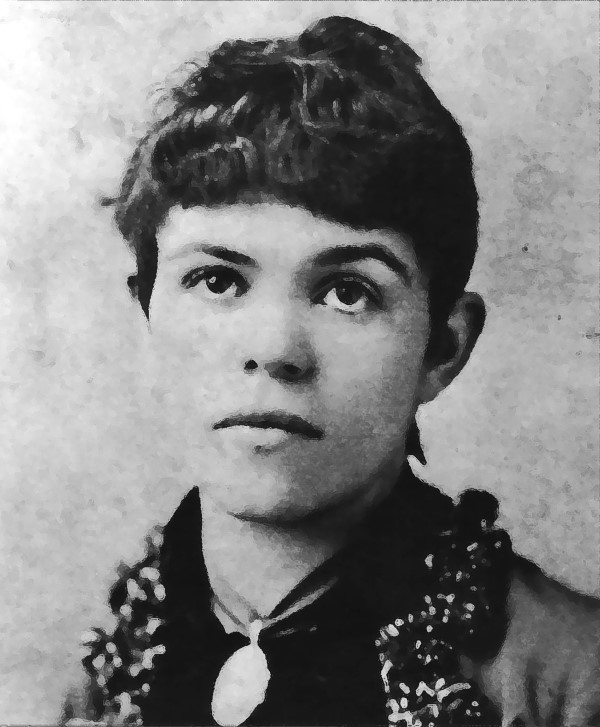

When the beautiful Adelaide Bartlett strode elegantly out of the Old Bailey in her widow’s weeds in April 1886, she had either succeeded in getting away with a murder that flummoxed the greatest medical minds of the Victorian era, or narrowly escaped the gallows after her husband poisoned himself.

On her acquittal, and to the contempt of the judge, cheers and applause erupted inside and outside the courtroom, where extra railings had been hastily erected to cater for crowds fascinated by the salacious details of the case known nationally as “The Pimlico Poison Mystery”.

Public opinion had dramatically turned in Adelaide’s favour over the six-day trial, and no-one, to this day, can explain how wealthy grocer Thomas Edwin Bartlett, 41, her husband of 11 years and 11 years her senior, came to have a substantial quantity of chloroform in his stomach that no trace could be found of in his mouth or larynx. Eminent surgeon of the day Sir James Paget quipped “Now that she has been acquitted for murder and cannot be tried again, she should tell us in the interest of science how she did it!”

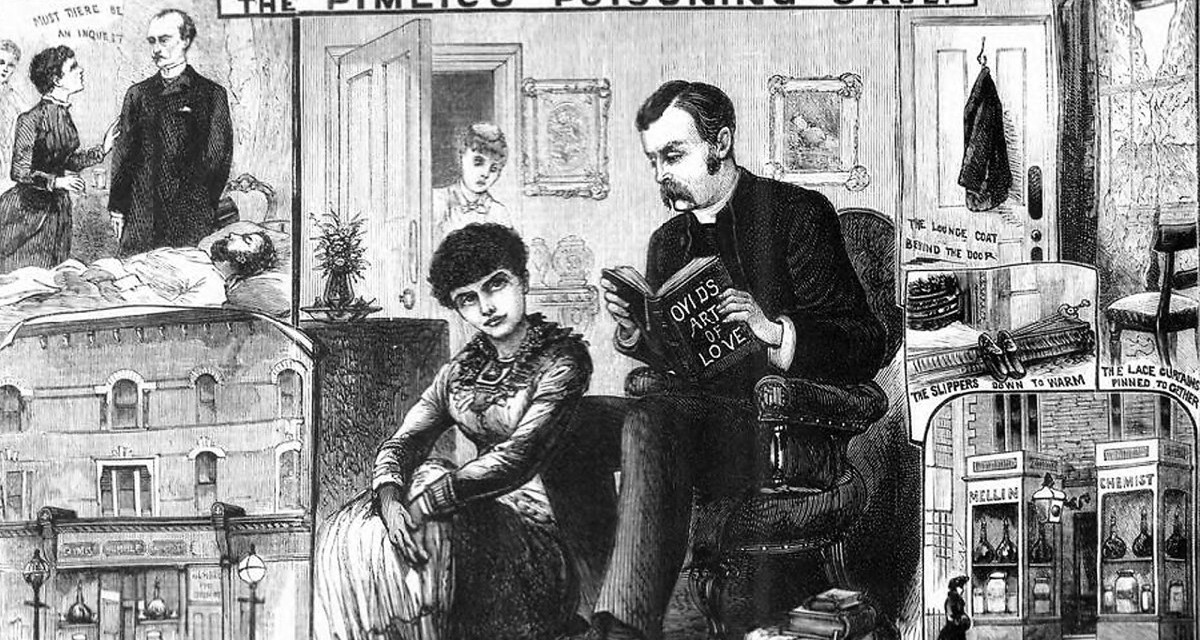

The case featured many lurid and unconventional factors, including Edwin’s outspoken views about having two wives for different purposes, and a menage a trois with Methodist minister Reverend George Dyson, who admitted to kissing Adelaide in front of Edwin. He would go on to purchase 4 small bottles of poison from four different chemists – apparently without thinking that it looked suspicious.

Edwin also claimed he was being hypnotised. He had previously blocked any doctor attending Adelaide during her only labour, which resulted in a tragic stillbirth. There was also the mystery of Adelaide’s high-ranking but shadowy biological father who, it was later confirmed, engaged leading QC Sir Edward Clarke to defend her and had paid Edwin a dowry on their marriage. Small wonder the Old Bailey’s capacity was breached.

In the early hours of New Year’s Day, 1886, Edwin died at 85 Claverton St, Pimlico. Adelaide attempted to revive him with brandy after waking as she slept at his feet. She had nursed him through his recent ailments of painful tooth removal and stomach complaints. His Doctor, Alfred Leach, was called immediately and the landlord woken.

Edwin’s father was also sent for. He immediately suspected Adelaide. He’d previously accused her of adultery with his younger son, Frederick, but later signed a formal statement of apology. He pushed for an inquest.

At the trial’s start, Attorney General Sir Charles Russell dramatically dropped all charges against the Rev George Dyson, who would now be the prosecution’s main witness. According to the laws of the day, Adelaide couldn’t give evidence.

On December 30, Dr Leach told Edwin he was nearly well, and needed no further medical help. The following day, the couple and Dr Leach visited Edwin’s dentist. The couple were affectionate, saying they wished they were unmarried, so “they might have the pleasure of marrying each other again.”

After a hearty supper of jugged hare, Edwin asked landlady, Mrs. Doggett, to serve him a large haddock for his breakfast tomorrow, saying “he should get up an hour earlier at the thought of having it.”

George testified that the three of them were close, producing loving letters from Edwin thanking him for his attention to Adelaide. He claimed Adelaide told him Edwin was dying and would die within a year. The three of them had an understanding that he would marry Adelaide on Edwin’s death.

The housemaid confirmed walking in on Adelaide and George in intimate positions at the house, where he kept his own slippers and housecoat. Edwin had also made George executor of his will. Initially he left his entire estate to Adelaide on condition that she did not remarry but redrew it four months before his death with the condition removed.

George claimed Adelaide asked him to buy a bottle of chloroform on December 27, to help Edwin sleep. She couldn't get it from Dr Leach because “he did not know that she was skilled in drugs and medicines, and not knowing that he would not entrust her with it.”

Dr Leach, who considered Adelaide a devoted, loving wife to her mildly hypochondriac husband, and an excellent nurse, testified she confided that she’d wanted the chloroform to wave in Edwin’s face, to stop him pursuing her sexually. She claimed that they had a platonic relationship and that her pregnancy was the result of one singular act, but he was now showing interest.

Adelaide had said: “He requested us, in his presence, to kiss, and he seemed to enjoy it. He had given me to Mr. Dyson.” She claimed she told Edwin of her intention to stop his advances, it was their last conversation – they didn’t argue. She admitted disposing of the chloroform.

Adelaide’s midwife confirmed Edwin wouldn’t allow a doctor to attend Adelaide’s labour, but her understanding was that the pregnancy occurred after one single act of ‘unprotected coitus’. We can imagine the outraged gasps later when it was revealed that no fewer than six condoms were found in Edwin’s coat pocket and a copy of a sex guide, of sorts for the time, found in his possessions.

No expert could explain how the chloroform entered Edwin’s stomach without any signs of a struggle or burning. Sir Thomas Stevenson, who confirmed chloroform was the only poison present, believed it could only have been self-administered. The jury were quick to acquit Adelaide.

Had Edwin gulped chloroform down quickly with intention, by accident, or under hypnosis? Or did noisy New Year’s Eve revellers and brandy cover the crime? Was Edwin a willing cuckold, did he believe he was dying? Were there other sexual relationships at play? Was Edwin homosexual? Was George as naïve as he appeared?

Most criminologists point the finger at Adelaide, but she faded into obscurity, never answering Sir James Paget’s question, and the Pimlico poison mystery remains just that.