Words: Adrian Day

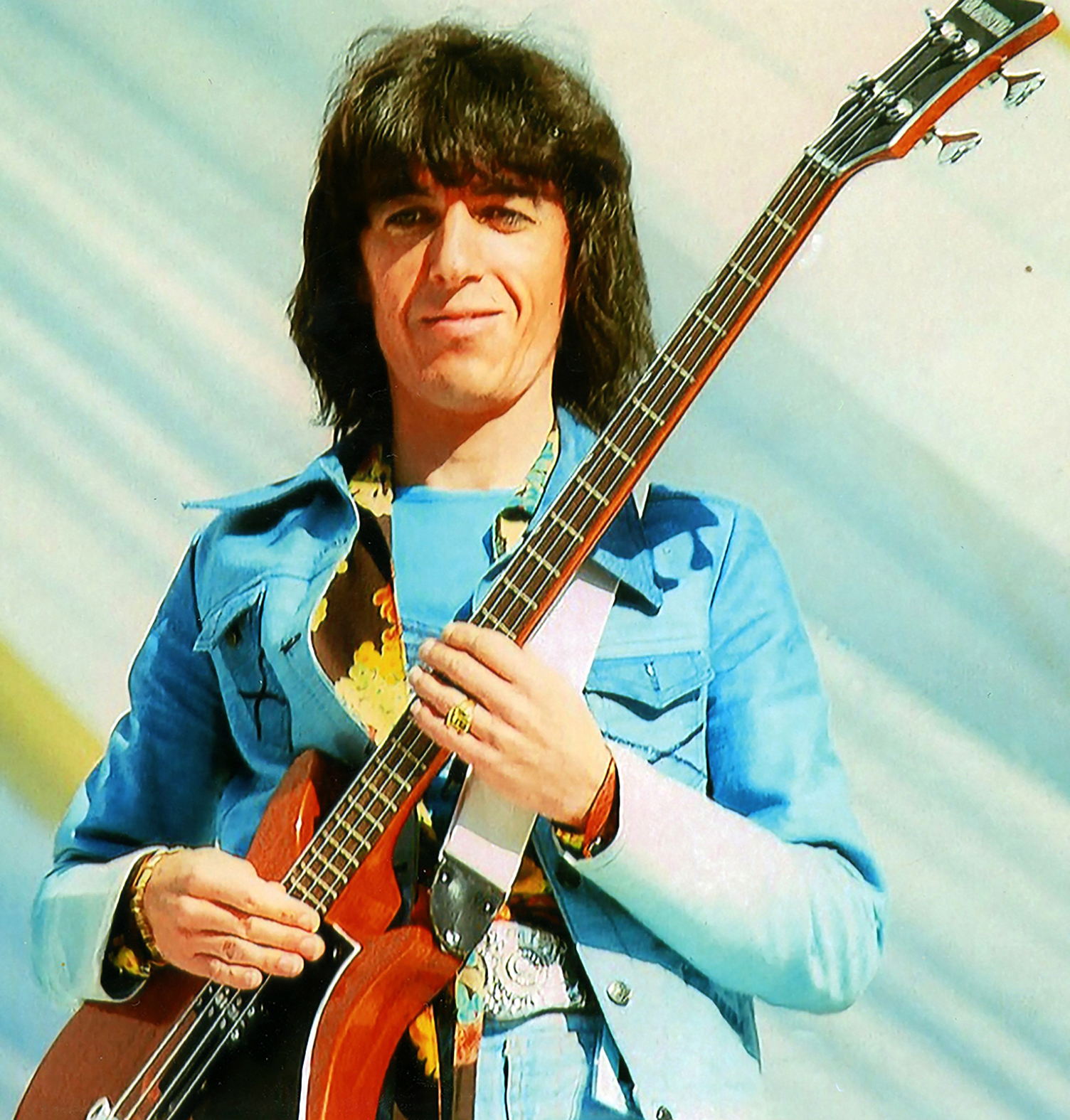

IT’S NOT OFTEN that you get the chance to shoot the breeze with a legend – but I’m sat in the Chelsea home of Bill Wyman, former bassist in the Rolling Stones.

Quiet and grounded, Bill believes that nine out of every 10 extraordinary artists are simply regular, good people who have interests and hobbies just as any non-famous person would.

Bill himself falls into this category, as an avid researcher and writer of all kinds of history. However, a long-time love of his is the local history of Chelsea.

“I originally started to write a history of London. But then I realised it was just too massive,” says Bill. “I had hundreds of books about London, hundreds of photos of London. But it was just too much of a project. I didn’t want to do a history of Chelsea because there’s a lot of books out there with old prints and things. I thought, ‘I want to do a book on the way Chelsea is now. What you can see if you walk down streets, what’s interesting for people just to walk and look around and think of Chelsea in a different way.’”

Bill considers himself an archivist and researcher, rather than a collector, and finds great joy in “delving and finding little bits of magic that I don’t think everybody knows,” he says. To do this, he focuses on both the landmarks of Chelsea at their face-value and on the stories that lie behind the buildings.

He has a lot of time for the renowned architect and former Chelsea resident John Samuel Phene but regrets that he doesn’t have a permanent memorial.

“They’ve got Phene Street dedicated to him. There’s the Phene pub where George Best used to go all the time. You know, he built the whole of Margaretta Terrace on a plague pit and a lot of Oakley Street, but do you know there’s not one plaque for him anywhere.”

The book itself is titled A Village Called Chelsea, and Bill has been gathering his research for it since 2002. Over the last 20 years he has taken “almost 2,000 photos”. However, having recently finished the book, he only ended up using around 400 of them. There was simply no room for any more. Bill views his book, when compared to the internet, as a singular, comprehensive work that is more suited to the task of informing those wandering the streets of the borough. Almost as an extension of his work, when he himself is meandering through the streets of Chelsea, he is often tempted to go over to people walking around and impart some of his historical knowledge, particularly when he sees they are missing out on things.

This desire to understand history, and to educate others, stems from his grandmother. He has an obvious and deep affection for what she did for him. Probably the most influential figure in his life, she instilled in him a desire to “give something to people who otherwise would not know what’s here.” Bill is certainly doing that, having written 11 books: “Most of them took me three, four years to do.”

People are often distracted today by technology which can take away from living in the moment, something that Bill learned the importance of when he was a child with his grandmother. As it is for all children, but particularly for Bill, his younger years were vivid as he grew up in south London during World War Two – an experience he is also publishing as a short memoir.

“I was bombed out and all that – machine-gunned by a German fighter bomber,” he says. “It’s called Billy in the Wars.”

Even after the war, Bill’s life was far from easy. His family home didn’t have electricity until he was 16 years old, and the future rock ’n’ roll star would eat all of his meals off government-sanctioned food rations until he was 17.

Bill is proud of his rise from poor beginnings, where his family would sometimes eat dandelion leaves “because there was nothing else to eat”.

“I’m proud to be a Londoner,” he says. “There were only two in the Stones – me and Charlie. The rest of them weren’t Londoners. Mick and Keith came from Dartford and Brian Jones was from Cheltenham, Mick Taylor was from Welwyn Garden City and Ronnie Wood was from West Drayton.”

From the point where he joined the Rolling Stones in 1962 and onwards, Bill reflects on the fact that “every time I did anything, I was always lucky and it was successful in an usual way.”

Indeed, his broad range of interests has led to many memorable moments, such as discovering a Roman archaeological site in Suffolk and playing charity cricket for several years with legends like David Gower and Michael Holding – even taking a hat trick at the Oval with his leg breaks and googlies.

However, of all the activities that he has embarked on and of all the great people that he has met during his life, Bill particularly values his connection with the Belarusian-French artist Marc Chagall.

While still in the Rolling Stones and living in Saint-Paul de Vence in Provence, Bill would find himself going to the home of Chagall. “I took hundreds of pictures of Chagall and even did two books on him. You know, he really was amazing,” he says of the pioneering artist, who was one of his dearest friends.

Signing off Bill says: “I always think everything’s preordained. It’s fate. It’s gonna happen anyway. I’ve had absurd miracles in my life, which could never happen, but they did. I was in the Stones for 31 years. I’ve been out for 30 – I was in The Stones for 31 years. I’ve been out for 30 – and I’ve been lucky enough to pursue all these other interests in that time.”

Bill’s book on local history, A Village Called Chelsea, is due to be published next year. We will be sure to update readers when publishing details are finalised.