Through its dedicated commission service, the Royal Society of Portrait Painters gives clients a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to be immortalised by the country’s most talented artists

Words: Will Moffitt

When Peter Kuhfeld’s portrait of King Charles III is unveiled, his depiction of our reigning monarch will fill newspapers, magazines and social media feeds. Inevitably a debate will ensue as to whether the king’s likeness has been honourably captured.

One thing that might get lost in the coverage is that Kuhfeld is not just a painter of royalty but of ordinary people too, and that – for the right price – his sharp eye and easel can come to your door.

Founded in 1891, the Royal Society of Portrait Painters – based in St James’s – has nurtured some of the UK’s finest portraitists, including John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler. Known for its summer exhibition at the Mall Galleries – commonly regarded as the largest and most significant portrait show in Europe – the society seeks to unearth nascent artists while supporting its regular members who are among the country’s most renowned and exclusive portrait painters.

Through its dedicated commission service the general public can enlist the services of about 50 of these artists, guaranteeing portraits of unparalleled quality, painted by masters of the craft who, like Kuhfeld, have worked on high-profile commissions. “I really love helping a client and seeing their dream and vision come true,” Martina Merelli, head of society commissions, tells me. “The most important thing is transparency. Making sure that the artist and client understand each other.”

The society’s commissions office sports a striking portrait of Queen Elizabeth II completed by longtime society member Antony Williams, who won the Ondaatje prize for portraiture in 1995 for his portrait of the Bishop of Guildford and works almost exclusively in the exacting medium of egg tempera.

In a corner of the office there are picture boards for each artist to help clients select their designated portraitist. One of them, a collection of works by Alastair Adams, sports the grinning face of former prime minister Tony Blair.

“We get a flow of people at the society’s annual exhibition who approach us and are fascinated by the idea of a portrait,” Merelli says. “We work out what they’re looking for, and we ask them to go through the boards or go online or through a catalogue, and select the artists who they feel best represent their vision.”

Other times commissions arrive via email, sometimes from esteemed institutions looking to celebrate or commemorate a person of note. In June, society member David Cobley’s affectionate characterisation of Sir David Attenborough was unveiled. Commissioned by the BBC, it shows the nation’s beloved broadcaster in a typically expressive pose; silver haired and clad in an olive blazer, those intense eyes fixing the viewer as an orangutan dangles from one corner of the canvas.

Like Attenborough, who met Cobley at his Richmond home, clients are required to do sittings where possible. Some artists just work from photographs while others strictly paint from life. “Some artists want to do a minimum of six sittings, but if that’s not possible, we’ll make it work,” Merelli says.

“People are busy so there is a limit, but I’ve had artists we’ve commissioned who normally do six or seven sittings and we’ve condensed it down to two sessions and they’ve used photographs to finish the portrait.”

One of the most moving commissions is a work by Adams undertaken for Peter and Helen Wellby. A beautiful and moving portrait of an adoring couple, it was commissioned by Peter after Helen was diagnosed with terminal cancer. Through Adams’ delicate brush strokes this tender relationship between a husband and wife has been preserved for ever.

Some portraits like Cobley’s By the Pool freeze-frame a single moment, capturing a second of pure joy as children leap hand-in-hand into a pool as their parents watch, smiling contentedly. Others use detail and symbolism to evoke information about the sitter beyond the superficial.

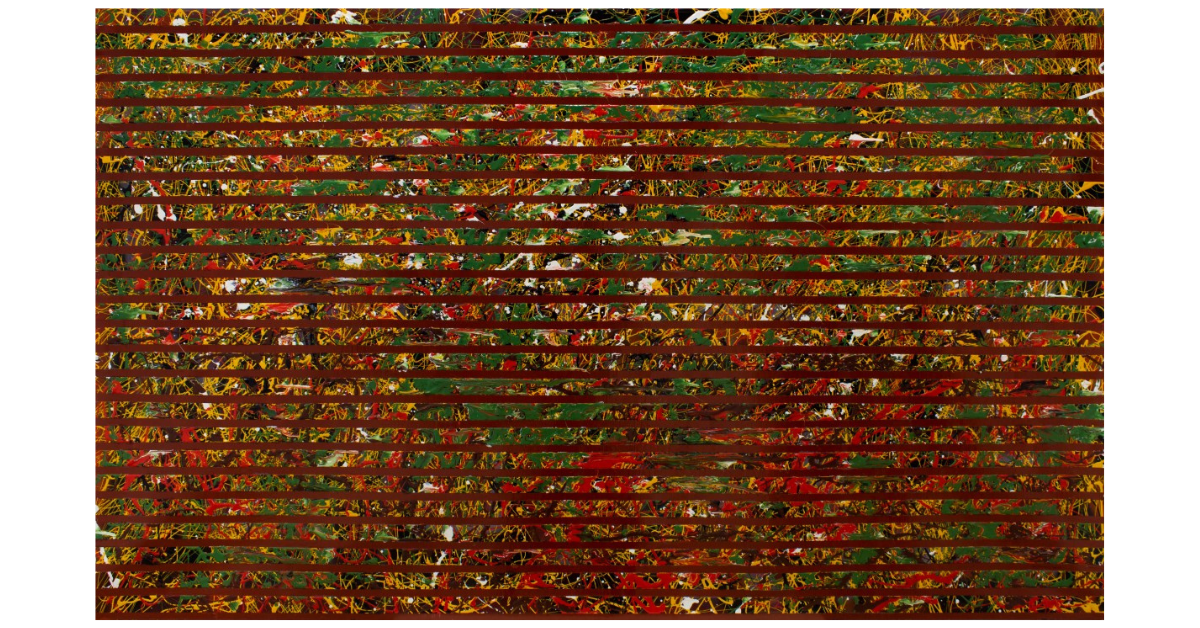

Using flowers, marbles and unique compositions, Miriam Escofet draws on the classical works of the past and the vanitas still lifes of the 17th century to imbue her portraits with subtly concealed biographical messages.

Connolly, a longstanding portraitist whose work is housed in many public and private collections – including the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, West Point military academy and the University of Oxford – talks of portraiture as a privilege.

“There’s a temporary intimacy that you get when you’re drawing or painting somebody that is just very resonant,” he says. “It has huge value.”