Discover the hidden history of Cabmen’s shelters, the green huts offering shelter, camaradermie and bacon to the capital’s cabbies

They are the intriguing glossy-green huts where bacon has sizzled and countless cuppas have been brewed for over a century; but if you haven’t got The Knowledge, you’re not getting in.

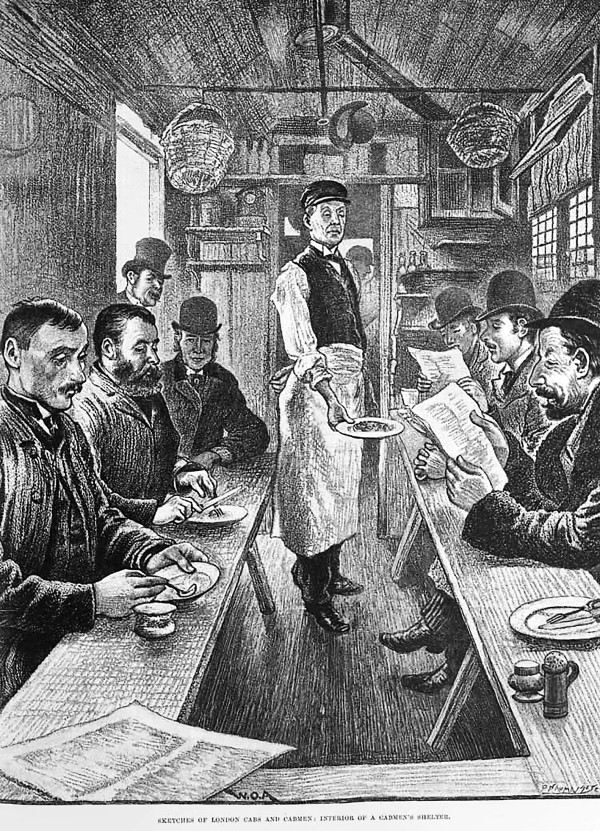

Scattered like emeralds across the streets of the capital, Cabmen’s shelters are little gems of London’s history. At their peak, they were numbered at nearly 70, dinky hut-havens humming with the chatter of the city’s cabmen as they sheltered from inclement weather or savoured a full English.

Motorisation, wartime and air raid damage have left just 13 green shelters standing – including at St George’s Square and Grosvenor Gardens, all now protected as Grade II listed buildings by English Heritage, and still run and protected by the same Cabman’s Shelter Fund that championed their cause in 1875.

Huts could be no larger than a horse and cart, as they stood on a public highway, catering for few more than 10 men at one time. They are all now painted the same green – Buckingham Paradise by Dulux, and entry nowadays is permitted only for Hackney Carriage licensees; Black Cab drivers who have all mastered the notoriously difficult exam known as The Knowledge – details about London’s streets that take years to study.

Non-Knowledge-qualified muggles are, however, able to sample the pleasures of a cabby’s repast through the takeaway hatch, where on any given day you might be queueing between an inquisitive tourist and a local music legend who’s popped out for a sausage and egg bap.

The Cabmen's Shelter Fund was established by several Victorian gentlemen under the presidency of the Earl of Shaftesbury, proprietor of The Globe newspaper, who reputedly set up a fundraising appeal after his servant was unable to find him a cab in the snow.

Cabbies had it tough. They were expected to sit ‘on the box’, exposed to the elements in sun, rain, sleet and snow. They weren’t allowed to leave vehicles unattended at the cabstand, and as their only shelter available was inside pubs, they had little choice but to pay for someone to mind their cab or risk having it stolen. Once inside, more money was spent on food or drink to claim a space at the fireside. In December 1874 The Globe appealed:

“Everyone is familiar with the wretched appearance of poor “cabby” while waiting patiently for a fare, or in vain attempting to transform some passer-by into that profitable commodity.

He stamps on the pavement, exchanges doleful jokes with his fellows, or, if he has not sufficient energy for these exercises, sits shivering and apparently meditating on the unsympathetic universe.

When the time for a meal arrives, his food is neither hot nor cold, and it but slightly cheers him.

His ills are, of course, tenfold increased at night, when there is probably a miserable fog, or it rains or freezes.”

The truth was that London lagged behind other cities, including Birmingham, where, ever at the forefront of industry and innovation, cabmen’s shelters constructed there years previously became the prototype for the London shelters, the first of which opened in Acacia Road, St John’s Wood.

Cabbies paid either one penny per day, or fourpence per week to secure the right to use any and every shelter in London, each shelter supplied with light, water, a stove and under the charge of an attendant to supply refreshments and preserve order. It is still prohibited to gamble, play cards or drink alcohol inside shelters.

The cabmen-only ruling was an Edwardian intervention. In April 1907 The Morning Post lamented Westminster City Council’s restriction of the use of cabmen's shelters to cabmen only. “A hundred circumstances conspire to throw a man into London late at night or early in the morning… He makes his way to the nearest cab rank and finds his man in a shelter aglow with light and rather stuffy with smoke. There is a smell of bacon or sausages or steak frying, and, to the weary wayfarer, it is appetising. Though he be a millionaire, he must crave for admission and food, for there is resentment of the average intruder, and if he finds the food good and the company interesting, and delays his departure for an hour or two, that is to the credit of the fast-disappearing race of men whose shrewdness and humour and knowledge of London are worth understanding.”

One century later, motorised tyres on tarmac have usurped hooves on cobbles; smog is no more, bikes and scooters abound, and still the conversation and the ketchup keep flowing within these beloved green bastions.