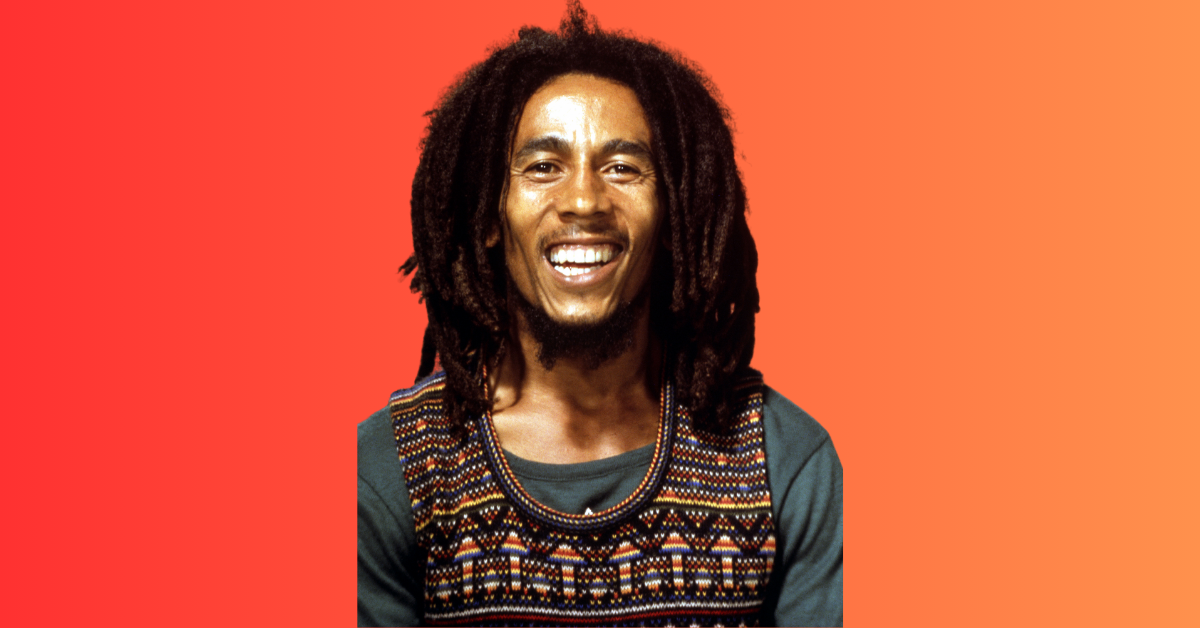

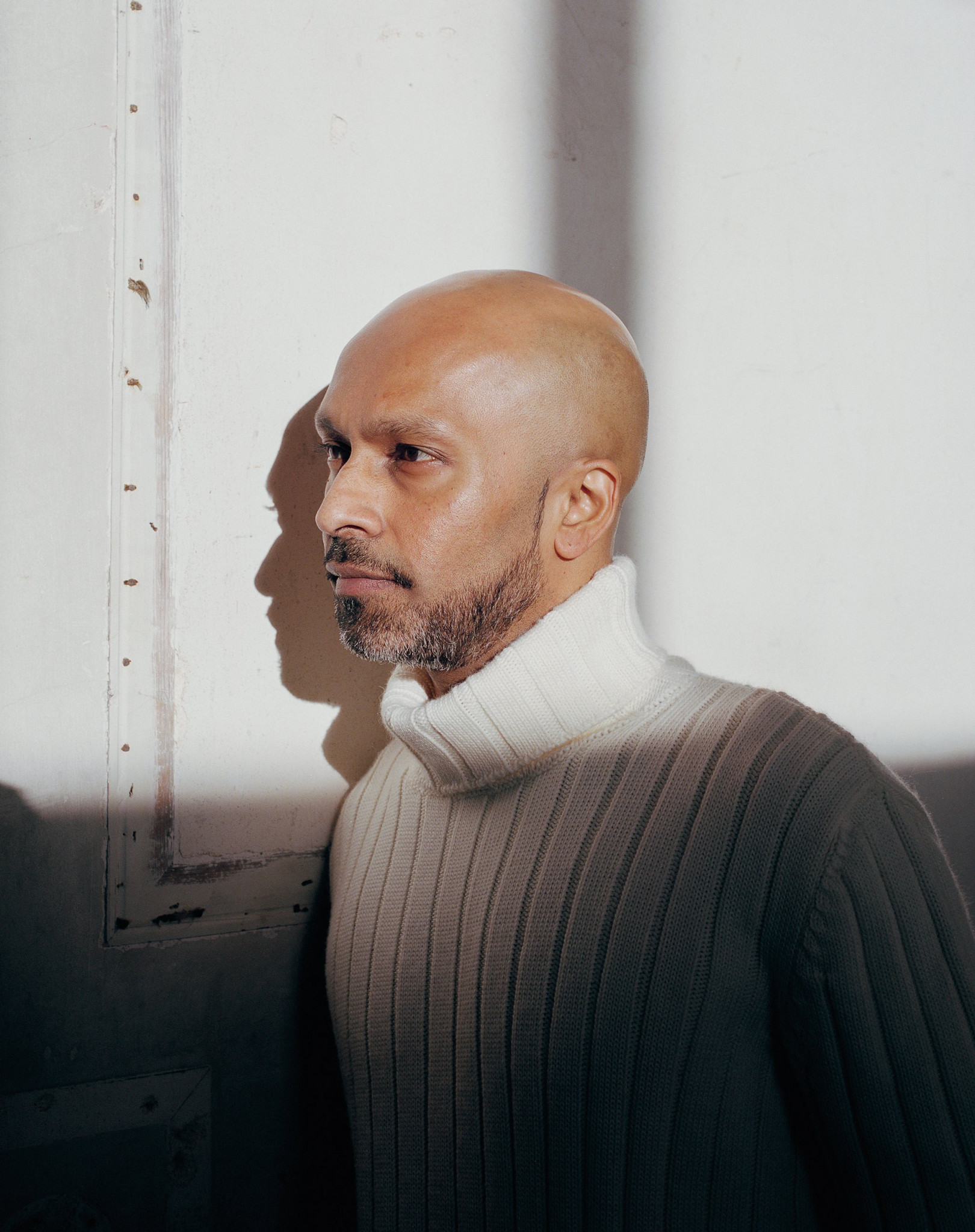

During lockdown, on the advice of his mother, renowned choreographer Akram Khan took time to pause and reflect on the past and emerged ready to feed into the future

Words Reyhaan Day

Akram Khan is one of the world’s most celebrated choreographers. His work, from productions created within the Akram Khan Company, for high-profile artists and musicians and for the 2012 London Olympics, has garnered acclaim and respect for its ethereal aesthetic, intensely political messages and combining of contemporary forms of dance with Indian classical traditions.

This year, the company celebrates two decades since its foundation. Khan, born in London to Bangladeshi parents, says that although looking back over 20 years at the forefront of contemporary dance is surreal, it has been overshadowed by the strange times in which we now live. “We wanted to celebrate the 20-year anniversary regardless of the situation, to give people a sense of journey and reflection. I feel like the situation we are in has forced us to stop.”

Khan says this was distressing; his life until lockdown had involved frequent travelling – gaining inspiration from working with artists across the globe and immersing himself in rehearsals. “I was really down about it for about five months. I stopped creating, because my movement stopped. I couldn’t connect with people.

“The silver lining was when I spoke to my mother. She said: ‘Change the word stop. Look at it differently. See it as a pause.’ If you look at this situation as a pause, it becomes about a moment of reflection. It gives you space to reflect in the past. By looking at the past, you can then feed into the future.”

Khan took this opportunity to delve into his company’s history – pulling together projects from the archives, commissioning new works and organising discussions that would form the basis of The Silent Burn Project – a multimedia, live-streamed platform that puts the spotlight on artists who have collaborated with the company in the past.

The bulk of the project involves productions from Khan’s roster of international dancers.

“We wanted to do something really poetic and sophisticated. We decided to film everything and then I would do what I do with the theatre and stage productions. We would rehearse things, practice things, we would edit things and then start to put things together with my team. It was quite an organic process.”

The discussions organised as part of the project revolve around two themes that have been central to the company’s work since its inception. “One is otherness, something I’ve always been exploring; and the other one is spirituality and God. We have two incredible talks by people that we’ve invited to be part of this. One is called Clouds of Witnesses and the other is called Hijacking God.

“I was always wrestling with the concept: do we serve God – because that’s how I see my parents – or does God serve us? Because that’s what I see in my generation. I wanted to explore that.”

Khan’s parents left Bangladesh in the early 1970s, just after independence. “My dad was already in London at the time, but my mother came in ‘73; she experienced a lot of the horrors of the independence of Bangladesh. The war was just insane – like any war.

Akram Khan and Sylvie Guillem in “Sacred Monsters” by Akram Khan & Sylvie Guillem at Sadler's Wells ©Tristram Kenton

“One of the things my family, aunties and uncles did – subconsciously – was treat my body like a living library. They could store their memories so not to forget their experience, their horrors; this was a way for them to grieve. This came in the forms of music, poetry, dance and theatre. My stage was the living room in my parents’ or my auntie’s house. We always had 30 or 40 aunties in the house at any one time – and they weren’t even my real aunties!”

This immersion into his parents’ culture formed the basis of a dance style that Khan has pioneered – honouring Indian classical dance like Kathak, while embodying a more modern approach picked up in the UK. At the beginning of his journey, however, this marriage of two worlds was not Khan’s intention. “It was other people that felt I was doing something unique. I was just following my curiosity, really.

“My contemporary teachers would say that I had something alien in me – another form, another language – they said that affected the contemporary but in an interesting way, and that I should explore that. That gave me the blessing and confidence to do so. Of course, later, my producer Farooq Chaudry helped create the structure of the company for me to be able to make the work that I want to make.”

Collaboration has long been a key part of Khan’s process. Over the years, he has worked with the likes of Danny Boyle, Anish Kapoor, Florence & The Machine and Kylie Minogue, among many others – each of whom has contributed to The Silent Burn Project in some capacity. “The moment I start a dialogue with someone, I feel like we’re moving towards something. I can have a dialogue with myself, but I’m not that kind of writer. My craft is not writing. You don’t work alone, you work with people and it’s about exchange.

“The most important thing for me was curiosity. I love to listen. When I’m talking, I’m not learning. One of the things we’ve lost as a civilisation is the art of listening. The patience to listen. Listening has been a very instrumental part of collaboration for me.”

Khan is the focus of a new Netflix series, MOVE, which puts the spotlight on influential and international dancers and choreographers. “I’m always a bit apprehensive… I’ve had so many documentaries done on me that it often just feels like another one. But with this, I felt that the directors’ vision was fascinating. They were moved by what I was doing, and I was moved by what they were thinking and what they wanted to create. Collaboration takes trust.”

“If I resist these opportunities, my work will only be seen through my vision. That means I’m not growing. If I trust it to be handed to another person, to be seen through another lens, then perhaps I can see my journey in a new way, and that’s very important.”

I ask Khan what the most memorable moment of his career has been so far – and his answer evokes his preoccupation with politics and the oppressed. “Something very personal. It was when I had the courage to say no to the OBE. It was a big moment for me. I never made it public.” While he previously accepted an MBE to please his mother, he told her that he wouldn’t be accepting the OBE – explaining: “I believe in equality and fairness; and if what I believe is what I’m presenting on stage, then my actions off-stage have to be the same. So I declined it.

“That was a really important moment for me to claim responsibility for what I say, my actions and what I believe in.”