When the Titanic sank on that fateful night in 1912, there were passengers with links to this area, where the ship was conceived, onboard

Words: Andy Williamson

It all began in Belgravia. It was 1907, the year that Rudyard Kipling won the Nobel prize in literature and Florence Nightingale, still going strong at 87, was awarded the Order of Merit by King Edward VIl. The summer social round was in full swing when J Bruce Ismay, the chairman of the White Star Line, received an invitation to a dinner party at 24 Belgrave Square. This grand London mansion on the square's southern corner, now the Spanish embassy, was the home of Lord Pirrie, chairman of Harland & Wolff, the Belfast shipbuilder.

Ismay – tall, slender and with a trim moustache – did not like the new high-society fashion for motor cars and so chose to travel to his host by horse and carriage. While the dinner was without reproach, Ismay had other things on his mind: how to compete with the Lusitania and Mauretania, the two liners recently launched by the rival Cunard Line. These two leviathans had grabbed the headlines and turned transatlantic boat travel upside down. At a stroke they had become the world's two largest passenger ships and, built for speed, they quickly grabbed the Blue Riband for the fastest Atlantic crossing, a title that Mauretania was to hold for 20 years.

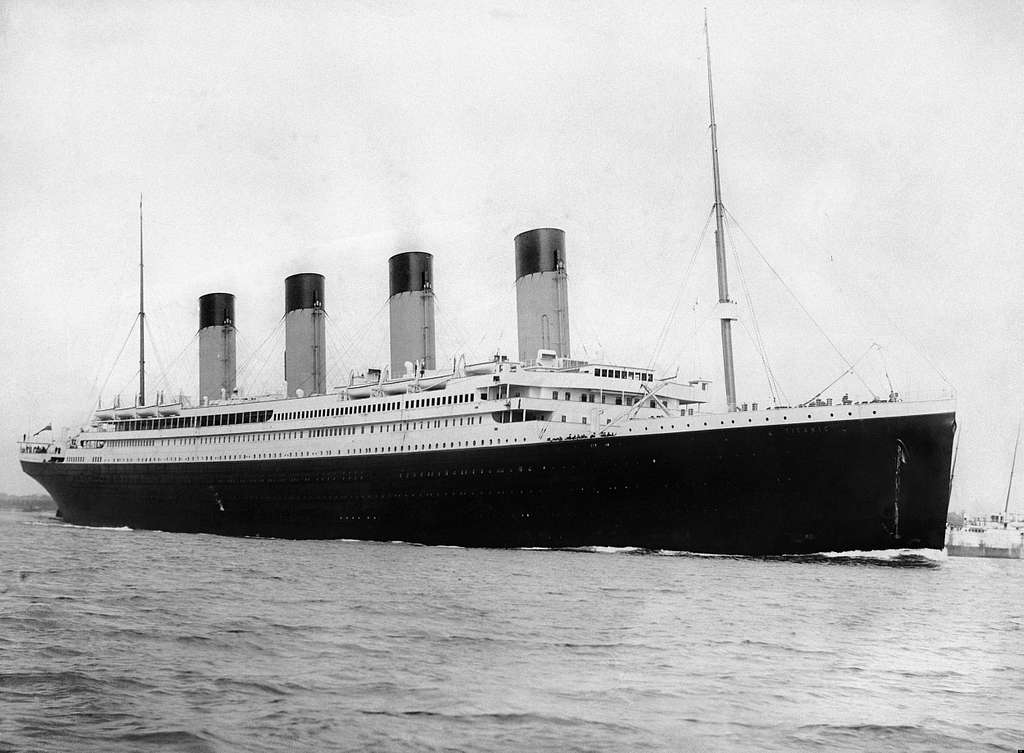

As the rest of the guests at Pirrie's mansion took their top hats and their leave, Ismay stayed behind. The two men had important business to discuss. The Cunard ships were undergoing sea trials ahead of their maiden voyages later in 1907 and customers were sure to follow. Ismay needed a response. Over coffee, the two business leaders sought a solution to this challenge. Their answer was the Olympic-class boats: three superliners that would not try to compete with their Cunard rivals for speed but instead would grab the world's attention, and pocketbooks, with their unparalleled luxury. The siblings were designed and built at Harland & Wolff.

The oldest was the Olympic, launched in 1911, the youngest the Britannic, completed in 1915, but it was the middle of the three, named after the immortals of ancient Greece, that history remembers. The Titanic, marketed as unsinkable, hit an iceberg on April 14 1912 during her maiden voyage and sank beneath the icy north Atlantic waters, causing the death of some 1,500 passengers and crew. Fate decided who died and who survived. It wove together many ordinary lives and made them extraordinary as a result of their common connection to the disaster, brought to life so vividly in James Cameron's 1997 blockbuster film that broke box office records.

Dipping into the lists of those onboard, we find many with a connection to Belgravia, Knightsbridge or Mayfair. There was Christopher Head, a first-class passenger. History often has a cruel sense of irony. Head worked as an underwriter at Lloyd's of London, assessing the risk of ships sinking. He was also heavily involved in local politics, being elected the mayor of the recently created borough of Chelsea from 1909 to 1911. Head was travelling to the US on business and, like a good underwriter, had his life insured for £25,000 for the trip. He died in the tragedy and is commemorated by a sundial in Cadogan Square Gardens, where he had been honorary secretary.

Another victim was the French cook, Pierre Rousseau. When he signed up to serve on the Titanic's maiden voyage he was living at 7 Frederic Mews, off Kinnerton Street. There were reports afterwards that the largely continental staff of the ship's restaurants were herded into their quarters by stewards and detained there. Only three survived. Rousseau got as far as the boat deck with his secretary Paul Maugé. However, when Maugé jumped into one of the lifeboats as it was being lowered, Rousseau, a large man, refused to follow suit.

The crew members onboard the luxury liner had a lower survival rate than the passengers, particularly those in first class. Belgian Georges Krins, who had spent two years before the voyage entertaining guests at The Ritz hotel in Piccadilly, was recruited as the bandmaster of the Trio String Orchestra, which played near the Titanic's Cafe Parisien. He was one of the musicians who stoically played music on the deck to try to calm the passengers as the ship went down.

Above: J Bruce Ismay & Ida Strauss

Another tale that has become part of Titanic lore is that of Isidor Strauss, co-owner of Macy's department store, and his wife, Ida. The American couple stayed at Claridge's before travelling to Southampton to board the ship. When women were being ushered into the lifeboats Ida demurred, saying to her husband: “We have lived together for many years. Where you go, I go.” The couple refused all efforts to change her mind and instead went and sat together on a pair of deck chairs.The highest-profile survivor on that cold April night was 49-year-old Ismay, the ship's owner.

He travelled down from his London home at 15 Hill Street, Mayfair, to Southampton in high spirits: just three weeks earlier his oldest daughter, Margaret, had been married at St George's, Hanover Square, and his wife and three youngest children came along to see him depart. When the iceberg turned his triumphant travel into tragedy he escaped in one of the lifeboats. Amid so much death and sorrow the newspapers needed a scapegoat: Ismay perfectly fitted the bill. In an age when it was “women and children first”, he was stigmatised as the Coward of the Titanic.

The shipping magnate resigned as chairman of the White Star Line in 1913 and spent the rest of his life in a state of depression, tormented by thoughts of how the disaster could have been avoided. He stayed out of the limelight, preferring to go fishing at his isolated property in Ireland that he had bought from Henry Rudolph Laing of Cadogan Gardens. Ismay's health declined in the 1930s after he was diagnosed with diabetes and he died at his Hill Street home in 1937 at the age of 74. This story, which had its beginnings in Belgravia, draws to a close in Knightsbridge. The funeral service for Ismay was held at St Paul's church the week after his death. The man who had conceived the world's greatest ocean liners was to be for ever associated with a night of tragedy.