To mark International Women’s Day on 8 March, Holly Kyte took a stroll around Chelsea to appreciate the ground-breaking female writers who have graced its streets…

Any feminist literary walking tour of Chelsea should start on Royal Hospital Road, in the footsteps of England’s first feminist writer. Mary Astell (1666–1731) settled in Chelsea in the 1680s, where she would write her pioneering pamphlets A Serious Proposal to the Ladies and Some Reflections Upon Marriage – the first, arguing for women’s intellectual equality with men; the second, imploring women to broaden their ambitions beyond marriage. Centuries ahead of their time, both espoused deeply radical ideas that riled patriarchal society. In 1712 Astell took a house overlooking the ‘Apothecaries’ Garden’, and later Cale Street. There’s no blue plaque marking all she achieved, but branching off Cale Street is one small nod to her life and work: Astell Street – a lasting remnant in Chelsea’s geography.

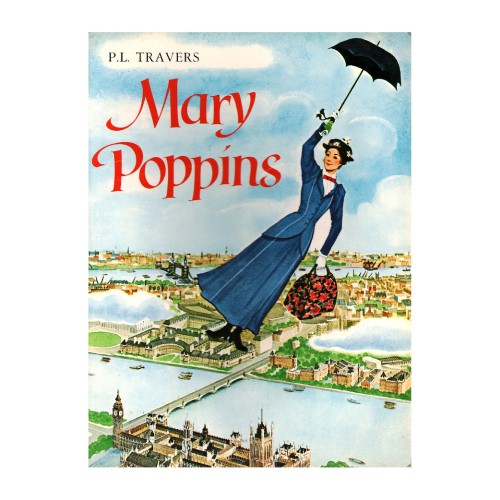

It was here, too, where she eventually negotiated the film rights to the books with Walt Disney, having resisted the idea for 20 years. It was a wise decision: Disney’s 1964 movie would turn Mary Poppins into an icon and ensured that Travers went down in literary history.

Continue down King’s Road and the next left is Oakley Street, where, at Number 87, Jane Francesca Agnes, Lady Wilde (1821–1896) lived. Best known as Oscar Wilde’s mother, Lady Wilde was a poet, an advocate for women’s rights and, like her son, no stranger to controversy. She wrote in support of the Irish nationalist movement under the pen name ‘Speranza’, arguing for independence and sovereign rule, but when she called for armed revolution in newspaper The Nation, she caused that paper to be permanently shut down.

Further along King’s Road, Paultons Square boasts another unconventional resident. Jean Rhys (1890–1979) – born in Dominica and famed for the masterful Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), which reinvented the story of Jane Eyre’s ‘madwoman in the attic’ in the British-ruled Caribbean – lived in Flat 22, Paultons House, for two years from 1936. Rhys wrote her acclaimed novel Good Morning, Midnight here, but its publication marked the start of a strange hiatus in her career, during which she disappeared for nearly a decade. She was found living in poverty in 1949 and would finally produce the novel that made her name some 27 years after her last.

The street can also claim the birth of one great Victorian novelist and the death of another. Elizabeth Gaskell (1810–1865), author of Cranford, North and South and the first biography of her friend Charlotte Brontë, was born at Number 93, though her residence would last just one year.

With the memories of such women waiting around every corner, the streets of Chelsea are steeped not just in history, but in the creative, progressive energy that these trailblazing figures left behind. That energy lives on in twenty-first-century Chelsea – a place where great women have always felt at home and been inspired to create ground-breaking works of literature.

Holly Kyte is the author of Roaring Girls: The Extraordinary Lives of History’s Unsung Heroines, out in paperback on 3 March. (HQ, £10.99)