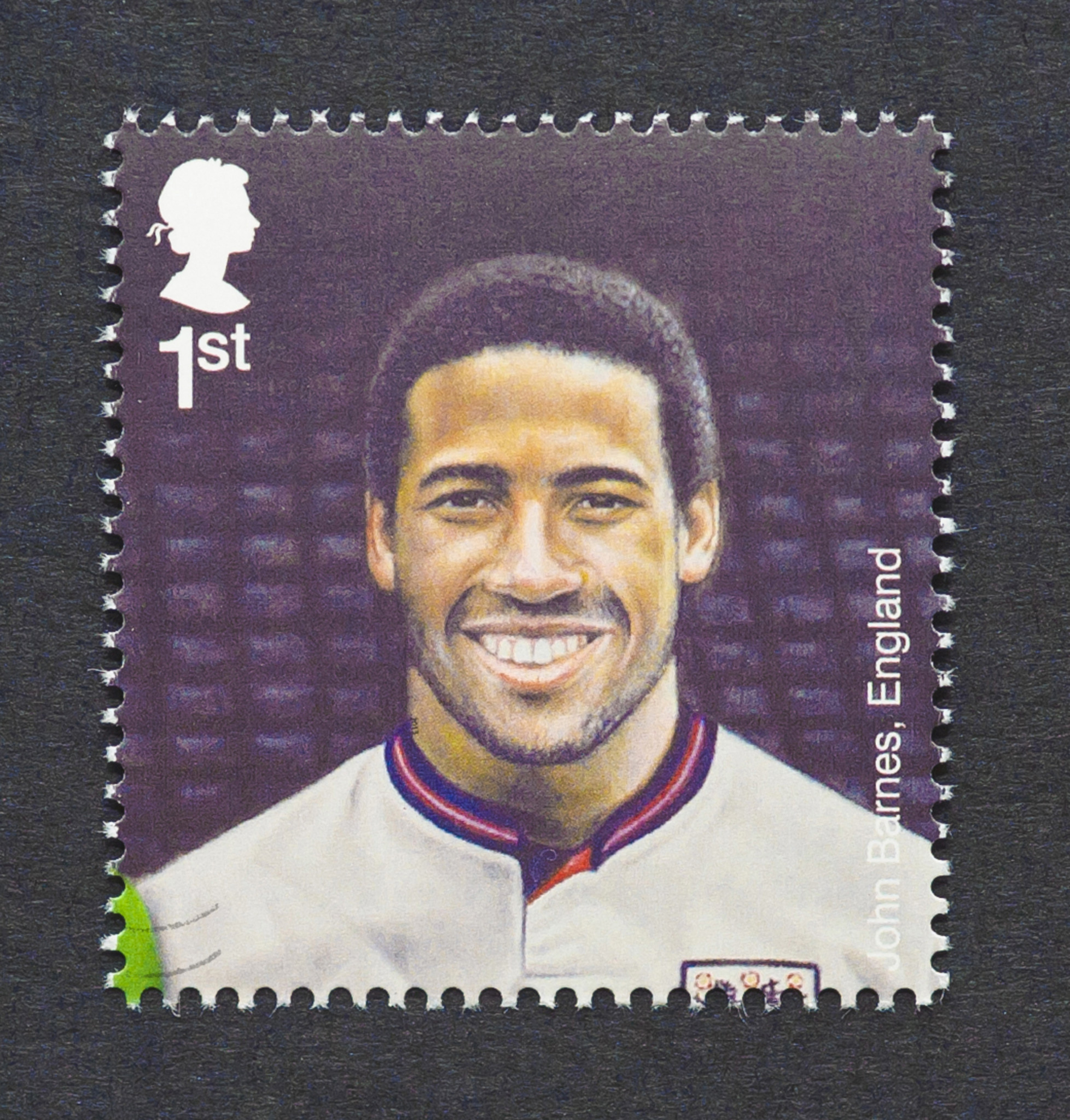

England and Liverpool legend John Barnes on football, sporting greatness, and systematic racism

Words: Will Moffitt

Life, John Barnes tells me, is “about maximising your potential.” The fast-talking former England footballer doesn’t really do small talk. We meet on a muted day at The Mayfair Townhouse, a regular haunt for the 58-year-old, who also enjoys spending time at The Arts Club and The Wolseley. Barnes, dressed in a black T-shirt and jacket, has made the trip down from the Wirral to fulfil his punditry duties and it’s not long until we are discussing the drivers behind sporting excellence.

Barnes attributes his determination and diligence to his father Roderick Kenrick Barnes, a former Jamaican footballer and military officer, who brought him up to be “stoic and resilient” in the face of adversity.

The paternal messaging paid off. On the football field Barnes stretched his physical and mental attributes to maximum capacity. A pacey left winger who caught the eye at Watford before excelling at Liverpool where he won the First Division and the FA Cup twice over, he scored 84 goals in 314 appearances for the reds. He played 79 times for England and – of the 11 goals he scored – one will forever be remembered. His slaloming run and deft finish against Brazil left the Maracanã open mouthed. Even today it still ranks as an all time great.

Barnes doesn’t remember much of that iconic goal in 1984. It’s a hazy blur. By his own yardstick he doesn’t miss playing either. “I missed it for a couple of years. A lot of people say they miss it, but they don’t want to train anymore. If I’m not prepared to put the work in, how can I miss it? I’m not being authentic.”

“What I do miss is being involved in management,” he adds. “I still think like a manager. When I watch a game I’m thinking about how I might better organise a team in terms of formations and tactics.”

Barnes' spell in management has not been as storied as his playing career. His tenure as manager of Celtic ended after eight months, while a successful period with Jamaica was followed up by a difficult and short lived stint at Tranmere Rovers. Despite the pressure and frustration that comes with the role, he still wants to manage, albeit in the right circumstances. “I want to be given an opportunity, not just given a job. Being given an opportunity is being given trust and time.”

Opportunity, particularly why some people are afforded chances while others are discriminated against, is a topic on which Barnes has spoken and written at length. His latest book, The Uncomfortable Truth About Racism, mixes personal experience with historical dissection to tease apart the root causes of racism and inequality.

Barnes draws on a wealth of historical and contemporary examples to support his thesis. He speaks eloquently and in rapid bursts shifting from topic to topic with remarkable fluency. During our hour length discussion we cover everything from Churchill and Gandhi to cancel culture and the refugee crisis.

He opens, not uncontroversially, by drawing attention to the inherent biases and blindspots that we all possess. Next he stresses that class and racism be framed together, not separately. “It’s not just about race or class or gender,” he says. “Look at the white working class, they have been discriminated against for years. If it’s just about race why are there so many poor white people?”

“The majority of racism is systematic, that’s why nothing much has really changed,” he adds. “As much as every now and then we elevate disenfranchised people into positions of power or status, that isn’t going to change the average persons’ daily life.”

While being the recipient – he strongly objects to the term victim – of racism during his career, Barnes’ upbringing taught him about the symbiotic relationship between class and privilege. Born in Jamaica he moved to Britain as a 12 year old when his father was appointed defence adviser to the Jamaican High Commission in London.

By Barnes’ own admission he had a relatively “privileged” childhood due to his fathers’ occupation, even if his family were not “financially rich”. He attended St Marylebone Grammar School and lived in middle-class areas such as Highgate, Golders Green, and in a four bedroom apartment above The Jamaican High Commission, then on St James’s Street. His club team mates did not have the same luxuries. “[I was] playing football at Stowe Boys Club in an inner city area with all these young black kids from housing estates,” Barnes says. “Football brought me into the reality of inner city life”.

Barnes' middle-class status did not deter incidents of racial profiling. Running through Hyde Park late at night he would regularly get stopped by local police. Meanwhile, in his book he recalls being shocked to see and hear racist ‘banter’ being dished out between his white and black teammates in his early days at Watford, aged 17.

Despite widely documented instances of racial abuse at elite level, however, football is one industry that Barnes’ feels is becoming more progressive. “Football is one of the least racist industries because there are only three per cent of black people in this country, and 30 per cent are black footballers,” Barnes says. “The best thing about football is that you now have average black footballers being footballers. When I was young you had to be a very good black footballer to make it.”

Unfortunately such representation is not mirrored in the dugout. Since the Football League was founded in 1888, only 28 black managers have worked in the English game. The Premier League has had 11 in 30 years.

“You have to change people’s perceptions,” Barnes says. “Not just black people, but women as well. You have to change the perception of a woman’s ability to run a fortune 500 company.”

“Once you change those perceptions you will see people being given proper opportunities,” he adds. “[The problem is that] what normally happens is when a black manager is unsuccessful we question whether he was ever fit for the job in the first place.”

Our conversation briefly turns to Barnes’ extracurricular pursuits. Alongside his punditry work, he has spent his post-playing days doing charity work, including being an ambassador for Save the Children, and fulfilling a range of media duties. In 2007 he impressed with his performances in the fifth series of Strictly Come Dancing, becoming the first male celebrity to receive a 10 from the judges. Was he nervous dancing on television in front of the nation?

“I don’t get nervous, even if I’m doing something that I can't do,” he says matter of factly. “It was hard work because I was training for four or five hours every single day, but my dad always brought me up saying ‘try your best and if you don’t make it, then don’t beat yourself up about it’.”

The Uncomfortable Truth About Racism, by John Barnes, is out now.