St Margaret’s Church is a much-loved local gem that has played a pivotal role in the history of power and politics

By Corrie Bond-French

Amid the grandiose architecture of Parliament Square, under the stony gaze of Westminster Abbey’s saints and gargoyles, St Margaret’s Church has, perhaps, been overlooked by many a visitor to the capital. Yet this medieval gem has borne silent witness in the high drama and history that has played out in this enclave of power and politics.

The great, the good and the notorious have featured in the church’s register of hatches, matches and dispatches. Marriages include recent Prime Ministers Winston Churchill and Harold Macmillan and literary greats including John Milton and abolitionist Ignatius Sancho. Poet John Keats bore witness to his brother’s marriage. Diarist Samuel Pepys married and indulged in extra-marital activity in St Margaret’s pews.

Pepys noted that it was at “The parish church” where he first heard common prayer. An entry from June 3, 1666 states: “I to St. Margaret’s, Westminster, and there saw at church my pretty Betty Michell, and thence to the Abbey, and so to Mrs. Martin, and there did what ‘je voudrais avec her…” Then on August 5, 1666: “Thence walked to the Parish Church to have one look upon Betty Michell”. On April14, 1667: to Margaret’s Church, and there spied Martin, and home with her…” And again on August 25, 1667: “…and to the parish church, thinking to see Betty Michell; and did stay an hour in the crowd, thinking, by the end of a nose that I saw, that it had been her; but at last the head turned towards me, and it was her mother, which vexed me, and so I back to my boat…”

Ignatius Sancho Samuel Pepys Oliver Cromwell

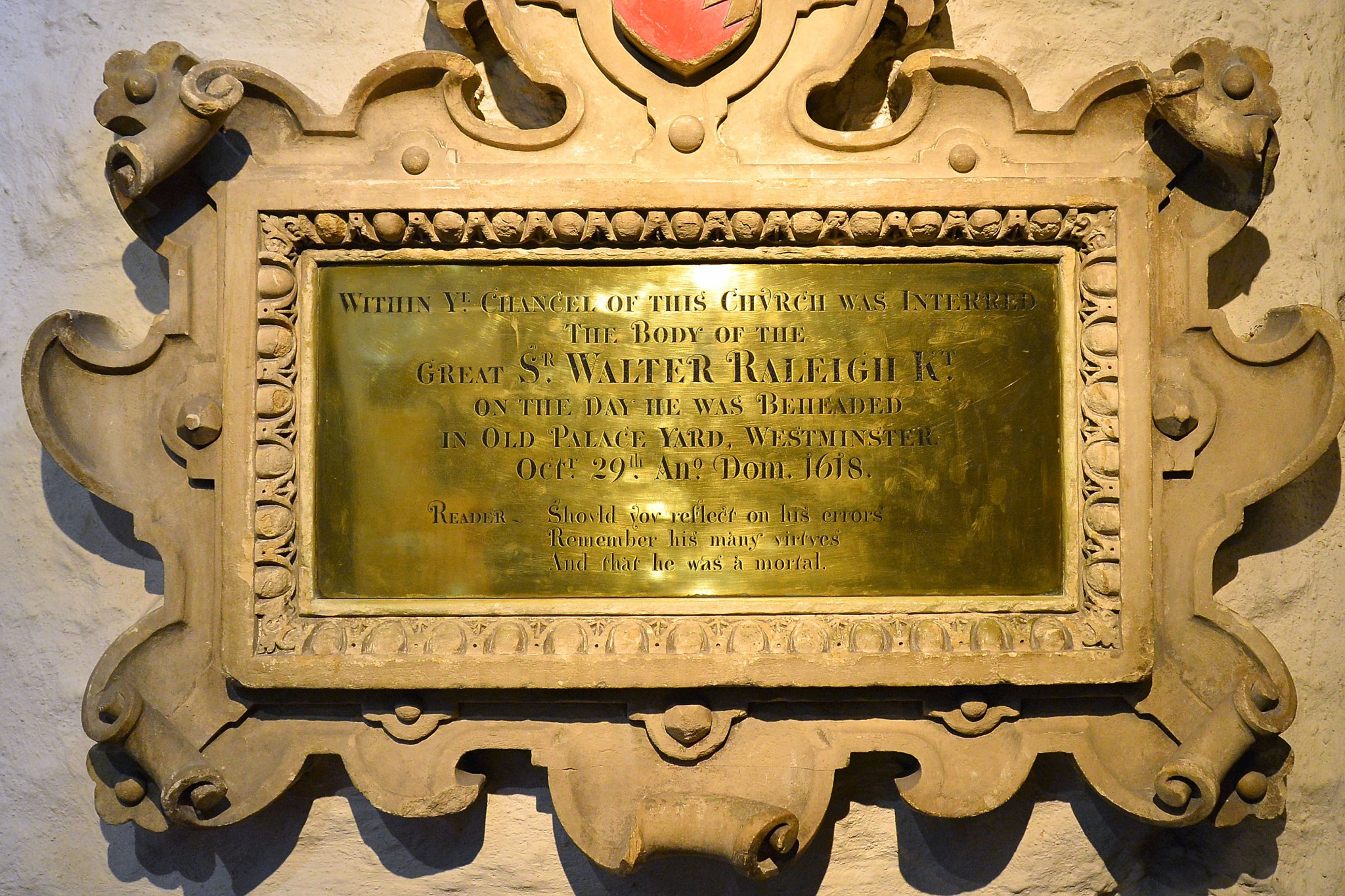

Printer William Caxton and engraver Wenceslaus Hollar are buried here. Sir Walter Raleigh’s body was buried here following his execution by beheading in Old Palace Yard. His head, however, was given to his widow Bess of Throckmorton, who reputedly had it embalmed and carried it around in a velvet bag.

When Charles II restored the monarchy after the civil war and interregnum, he took posthumous revenge on his father’s enemies; the bodies of a dozen or so of Oliver Cromwell’s associates (some 59 MPs had signed Charles I’s death warrant) were disinterred, burned and buried in the churchyard. Oliver Cromwell’s body, with those of John Bradshaw and Henry Ireton (Cromwell’s son-in-law and parliamentary army general) were removed from Westminster Abbey, their corpses were tried for high treason and symbolically beheaded on 30 January, 1661 – the date of Charles I’s execution 12 years previously. The bodies were then thrown into a pit, or common grave, in St Margaret’s churchyard while their heads remained on a 20- foot spike at Westminster Hall until a storm in 1685.

Originally constructed in the 12th Century – possibly earlier- by the Benedictine monks of what was then St Peter’s Abbey, St Margaret’s fell into disrepair and was rebuilt from 1486 at the behest of Henry VII, the first Tudor monarch, whose gimlet eye also had grand designs on the neighbouring Abbey.

“Sir Walter Raleigh’s body was buried here following his execution by beheading in Old Palace Yard”

Work was eventually completed in Henry VIII’s reign, and the church, named after St Margaret of Antioch, was consecrated on 9 April, 1523 over a decade before the birth of Elizabeth I, the break with Rome and the dissolution of the monasteries. At around the time that the Tudor boy-king Edward VI succeeded his dread sire in 1548, his uncle, Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, took it upon himself to recycle the very fabric of the church building to construct his new palace, Somerset House, in The Strand.

But the Duke hadn’t reckoned on the fierce resistance of the church’s parishioners, who, in an early example of church-hugging environmental protest, took up arms to defend their church from an act of selfish vandalism – and won.

By 1560 Elizabeth I ensured that St Margaret’s became a royal peculiar – a church directly responsible to the sovereign, alongside Westminster Abbey. In 1614, St Margaret’s became the parish church of the Palace of Westminster when parliament’s puritans eschewed the Abbey’s more liturgical form of worship.

In time, an additional chapel of ease and burial site was used as an extension of the parish on the site of Christchurch Gardens in Victoria Street – where the exact site of Ignatius Sancho’s burial is marked. With a history that inspired at least two former curates to write historical accounts, St Margaret’s served as a parish church for the locality through tumultuous times, and many more humble parishioners feature in its records.

There is Cornelius Vandun, a soldier who fought alongside Henry VIII at Tournai who then went on to be a Yeoman of the Guard for Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I, dying in 1577 at the grand old age of 94. And Joane Barnett, 82, buried in 1674, used to sell oatmeal cakes by the church doors and left money for the widows of the parish. A large oatmeal pudding was thereafter stood at ‘the feast’ in her honour.

More recently, the church hit headlines last year when it was announced that, owing to the Abbey’s depleted funds, there would no longer be Sunday services, and that the congregation and the choir would now integrate into Westminster Abbey’s services. This provoked uproar. St Margaret’s is no longer, technically, a Parish church, but clearly it remains a beloved local one.

Pictures of the church and plaques courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster