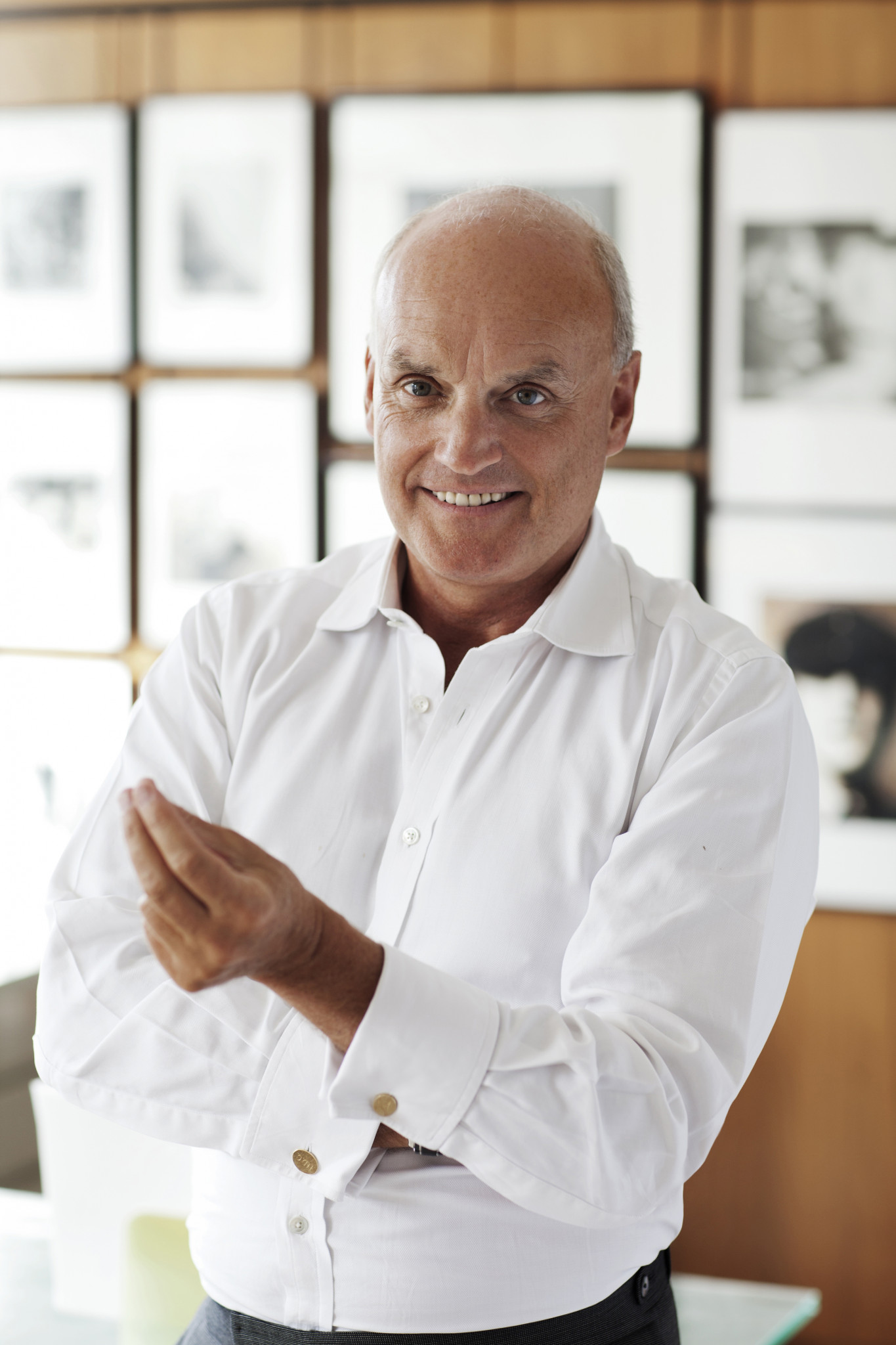

The former head of Condé Nast, Nicholas Coleridge CBE, talks to Cally Squires about magazines, museums and selective memoirs

Long-time Chelsea resident Nicholas Coleridge may have retired from full-time duties at the helm of Condé Nast but is as busy as ever writing books and chairing both the The Victoria and Albert Museum and The Prince of Wales’ Campaign for Wool.

Not even Covid could slow him down for too long. He contracted the virus back in the first lockdown and was hospitalised for 12 days.

“I got it quite badly but recovered fast and was desperate to get out of hospital and home,” he says.

Home then was the family’s country house in Worcestershire, with his wife and all four children, plus a merry band of various girlfriends and boyfriends. Despite the illness, Coleridge remembers it as an enjoyable and happy time with glorious weather.

He enjoyed lockdown two rather less. “I find I miss my friends; I miss restaurants, I miss parties and laughter. You can only watch The Crown and The Queen’s Gambit so many times. I couldn’t wait to get back to Ziani’s, Stanley’s and The Colbert.”

Coleridge grew up in Chelsea Park Gardens and has lived in the area most of his life, aside from a decade-long stint in Notting Hill. “I have always loved the Chelsea vibe, less glitzy than Notting Hill. I love Battersea Park too, and the bridges –Albert Bridge especially – and the Embankment and all those streets between the King’s Road and the river.”

You might spot him, not on foot these days, but nipping through the back roads to Mayfair on a recently purchased electric scooter. “The Wolseley and Oswald’s are often my destination.”

Further afield, Coleridge managed a summer holiday in Florence, but longs for further-flung adventures again. “One of the blows of lockdown was having to cancel a trip to Australia, where I was going to make a series of speeches about wool, in sheep stations across the outback. And then a trip to Jordan was postponed – we were going to the wedding of one of my godsons to a Jordanian Princess.”

“Oddly enough, I tend to forget episodes with tricky people”

It’s no surprise for a man who was out every night rubbing shoulders with the great, good and gorgeous – one of his goddaughters is Cara Delevingne – during a glittering career that has produced anecdotes casually ranging from a lunch with Princess Diana to a spat with Mohamed Al-Fayed, all of which can be devoured in his memoir The Glossy Years, published in 2018, and now available in paperback.

Has he put pen to paper on the next tome? “My next book will be a novel. I have thought of a plot at last and am refining it. I expect to begin writing in earnest this January. It’s about crime, sex and museums.”

Coleridge is an optimist about the future of the magazine business, predicting that successful glossy mags like Vogue, House & Garden and The World of Interiors will continue for a long time. “It is hard to replicate their special qualities, the beautiful paper, the photography, the instinctive navigation. Much more satisfying than reading on a phone. The strong should survive and prosper.”

His chairmanship of the V&A is covered by The Glossy Years. The pandemic has necessitated Zoom and Teams calls with the Department of Culture, trying to press The Treasury for emergency funds.

The national museums normally raise more than half their money themselves, and the other half from an annual government grant. “When we have no visitors, and our shops and restaurants are closed too, we are thrown into financial turmoil,” explains Coleridge.

Ensuring the V&A’s 2.7 million treasures are safe, along with not going bust, “required a lot of thought”, admits Coleridge, adding that he relished the challenge.

Looking on the brighter side, Coleridge recalls it being “magical” to “walk through the empty, echoing halls and see all the treasures waiting there. The museum was cleaner than I have ever seen it. And the newly-restored and re-lit Raphael Gallery is fabulous, and has to be seen”.