Formed as a secret society, its painters began signing their works with the PRB initials; and in the process, founded an artistic movement that was to shake up the British art world.

William Holman Hunt, James McNeill Whistler and Dante Gabriel Rossetti – three founding members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood – lived at 5 Prospect Place, 101 Cheyne Walk and 16 Cheyne Walk respectively.

Attracted to the area by low rents, studio space and access to the inspiration-giving river – while still remaining within easy reach of the West End and prospective buyers – the Cheyne Walk artists found themselves in a community of like-minded thinkers. Joseph Mallard William Turner had seen out his days here, living secretly with his mistress in accommodation on Davis Place, which later became 118-119 Cheyne Walk; but the artist’s private nature meant that his presence went unnoticed by other artists beginning to move into the area.

Cheyne Walk has enjoyed the greatest concentration of artists in Chelsea since the mid-19th century. From lesser-known painters such as Walter Greaves – born on the Walk and whose father had been Turner’s boatman – who enjoyed a brief glimpse at Chelsea’s artistic community, living at 104 Cheyne Walk, before being largely shunned and dying in poverty; to landscape painters Cecil Gordon Lawson and Edward Arthur Wilson; leading British impressionist Sir Philip Wilson Steer; and more recently, cartoonist and impressionist Sir Gerald Scarfe.

Many others of a similar disposition took up residences in nearby Glebe Place, Tite Street and Manresa Road – the location where, later, the Chelsea College of Arts began; and where Trafalgar Studios, one of the first and most significant of Chelsea’s emerging multiple studio spaces, was first opened in 1878. The building of studio space such as this attracted artists of varied income – important in lending Chelsea its bohemian, artistic air.

Similarly, The Studios on Tite Street created its own enclave of artists, including Whistler, John Singer Sargent and Augustus John. The influence of these large units spawned a series of smaller studio groups around the King’s Road and Glebe Place; and soon led to a healthy environment for artists and art lovers, with regular life classes and sessions with some of the era’s now-lauded names.

The Pre-Raphaelites would have a significant impact on a later but equally important era of art culture in Chelsea: the 1960s. In the years between the dissolution of the Brotherhood and the mid-20th century, the movement and its principles fell out of favour with those in artistic circles – particularly the emerging British Modernist movement – with the Pre-Raphaelite preoccupation with medieval imagery akin to the passé ideal of painting fully representing reality. But the technicolour aesthetic of ‘swinging’ London in the sixties generated a renewed interest in the movement’s work; while Chelsea artists in this age took bold new steps into unchartered territory.

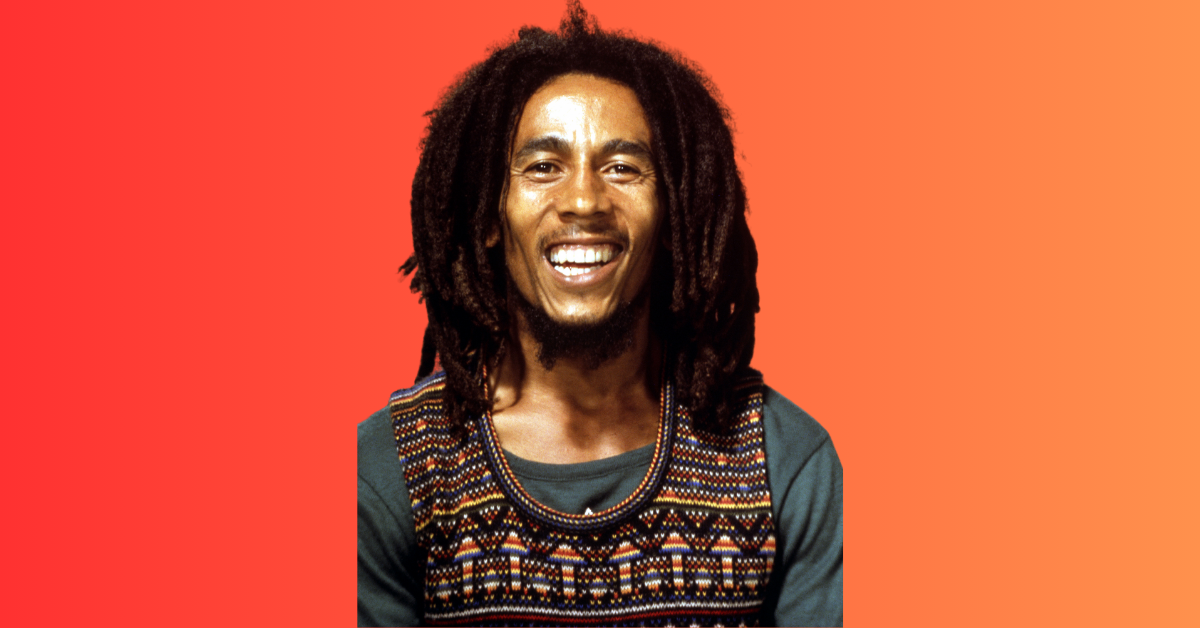

In the 1960s, Chelsea became home to some of the decade's most in-demand photographers – namely those immersed in the countercultural revolution taking place along the King's Road. Terence Donovan based himself in the area in the mid-sixties, opening hip outfitters The Shop at 47 Radnor Walk with designer Maurice Jeffery – a boutique that a 1965 issue of Rave magazine described as “a favourite of the ‘in' crowd”. Donovan was one of the first celebrity photographers alongside David Bailey – and his groundbreaking fashion images paved the way for a generation of photographers to come.

Fellow photographer Robert Whitaker's studio was also located in Chelsea, on The Vale. Over two years from 1964 to 1966, Whitaker intensively documented the public and private lives of The Beatles. The band's Yesterday and Today cover, with its surrealist shot of John, Paul, George and Ringo accompanied by dismembered dolls and raw meat, was taken by Whitaker in his studio. When The Beatles announced that they would no longer tour and had holed up in Abbey Road Studios to record Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, Whitaker moved on to another project. Now based at well-known residential studio space, The Pheasantry, on the King's Road, he teamed up with friend and pop artist Martin Sharp to help create the album artwork for Disraeli Gears – the seminal LP by Eric Clapton's band, Cream. The success of this project led to Whitaker's frequent collaborations with the underground magazine, Oz; an influential, tripped-out countercultural rag, considered one of the era's most visually exciting documents.

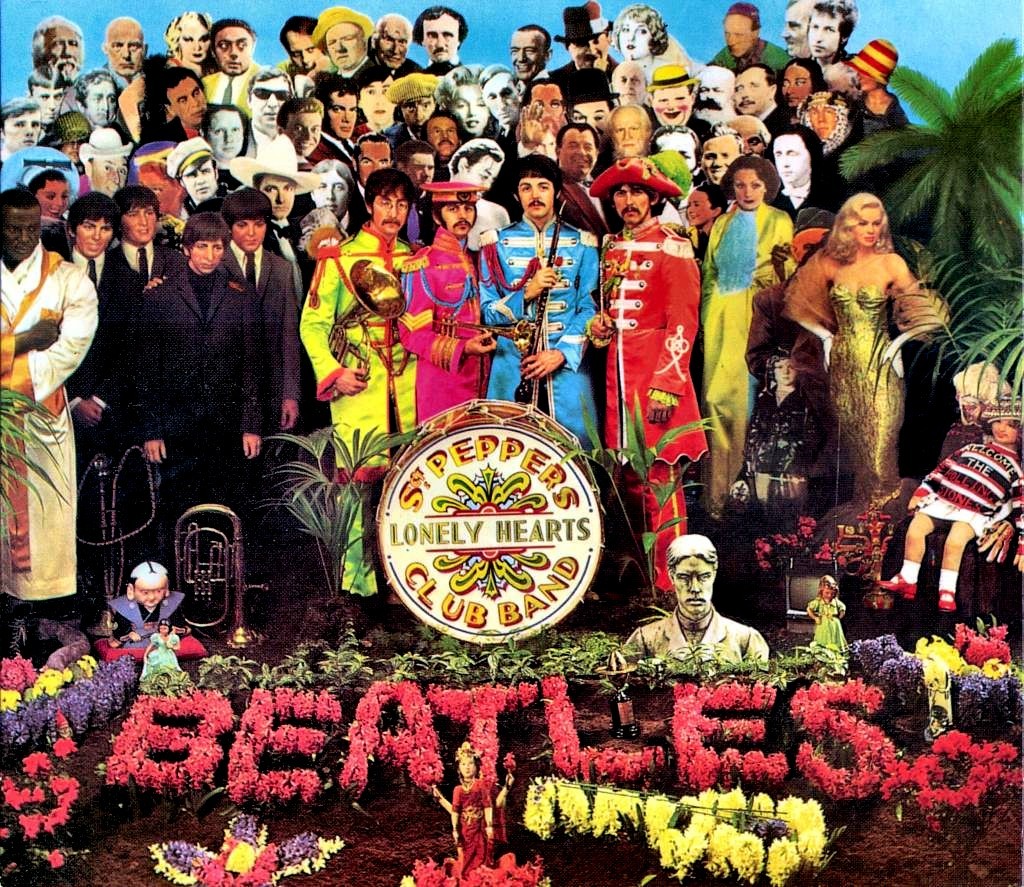

Photography gradually became the artistic expression of choice during this era, and other respected names found themselves living and working in Chelsea. Chelsea Manor Studios – which had originally opened in 1902 – was the location of Michael Cooper's studio. Occupying Studio 4 of the building, Cooper was set a task that would be his making – to put together the infamous photographic montage for the sleeve of The Beatles' masterpiece, Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Taking place in March of 1967, the shoot required wax figures from Madame Tussaud's, various props and collage items and the band themselves; Cooper's photograph was then painted by Peter Blake and Jann Haworth to achieve the final, eye-catching cover. Cooper, who was a significant figure in the music scene of the day, was also responsible for the lenticular cover of former Chelsea residents The Rolling Stones' experimental 1967 release, Their Satanic Majesties Request.

The increasing perception of Chelsea as London's most ‘happening' district directly led to the area's gentrification. Understandably, many of the artists initially drawn to Chelsea's bohemian, cutting edge atmosphere were priced out – with many artists' studios closing. Chasing affordable rents, creatives moved to nearby Notting Hill and towards Camden – leaving Chelsea with a rich artistic heritage, but less of an active community of working artists.

One of the few that continued living and working in the area was Julian Barrow – who worked for almost 50 years in the same Tite Street studio as John Singer Sargent and Augustus John, until his death in 2013. The demand for converted studio houses is such that they now command prices in the millions. Landlord Cadogan has, however, attempted to keep the bohemian traditions alive in Chelsea, by protecting some of the studio spaces for use by those in the art world.

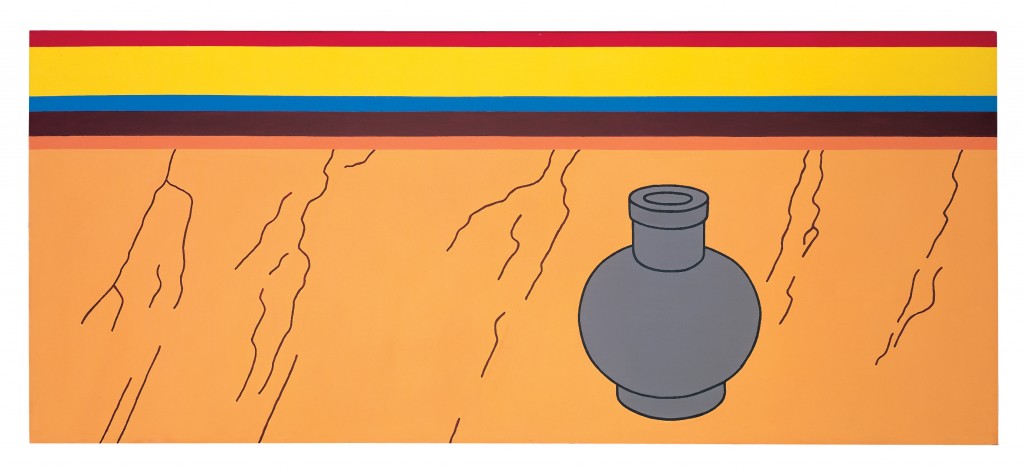

Though there were less artists residing in the area, a number of commercial galleries began to open – smaller than in the traditional art nucleus of Mayfair; and the success of societies such as the London Sketch Club, the Chelsea Arts Society and the Chelsea Arts Club, as well as the Chelsea School of Art (now Chelsea College of Art), continued the artistic traditions established in the area. Notable alumni from the art college include art critic John Berger, Quentin Blake, Patrick Caulfield, Peter Doig, David Hockney and many others.

Influential and prominent artists of the time, such as master British abstract painters John Hoyland, Howard Hodgkin and former student Caulfield, taught their skills at these institutions, impressing their styles upon future artists. With the increase of wealth in Chelsea during the 1980s and 1990s, the galleries became more professional endeavours – with collectors heading to Chelsea for its boutique vibe and stylish, high net worth local clients.

The influence of the area's historic art scenes is still felt in Chelsea today, with a number of galleries promoting the works of emerging painters, photographers and sculptors, as well as more recognised names. Langton Street, towards the World's End Estate, has had a long line of galleries occupy the street – a tradition that continues today, with 9 Langton Street exhibiting contemporary works by London artists whose stars are rising. The Little Black Gallery on Park Walk upholds the photographic traditions of Chelsea; home to works by the late, iconic photographer Bob Carlos Clarke, one room at the gallery is permanently dedicated to his irreverent photographs. Michael Hoppen Gallery, on Jubilee Place, also showcases the best emerging photographers, alongside established masters of the form.

Chelsea's reputation as an artistic hub has been revitalised further thanks to the opening of Charles Saatchi's world class Saatchi Gallery – originally opened in a disused paint factory in St John's Wood in 1985, it moved to the South Bank for two years in 2003. Forced closure left the gallery without a venue for three years, but in 2008, the Saatchi Gallery found a permanent home in Duke of York Square.

A 70,000 sq ft space, it has been a significant addition to London's art scene, with the gallery hosting five of the six most visited exhibitions in London in 2009 and 2010. The gallery has become known for showcasing works from internationally acclaimed artists as well as those unknown to the art world, in exhibitions focusing on new art from regions such as China and the Middle East.